review

Haaretz

The Price She Paid

In the first third of her book, Suzy Eban offers up a scrumptious portrait of her early years in Egypt and of courtship with the future foreign minister. When she moves on to life as Mrs. Abba Eban, however, she adopts an unfortunate reticence.

This memoir by Suzy Eban, the widow of Israel’s iconic premier diplomat and foreign minister, Abba Eban, gives one pause to reflect on how daunting autobiographical writing can be and why so many leading lights employ ghostwriters, acknowledged or otherwise, to frame their stories for them. The result of Eban’s efforts at the genre are frustratingly uneven.

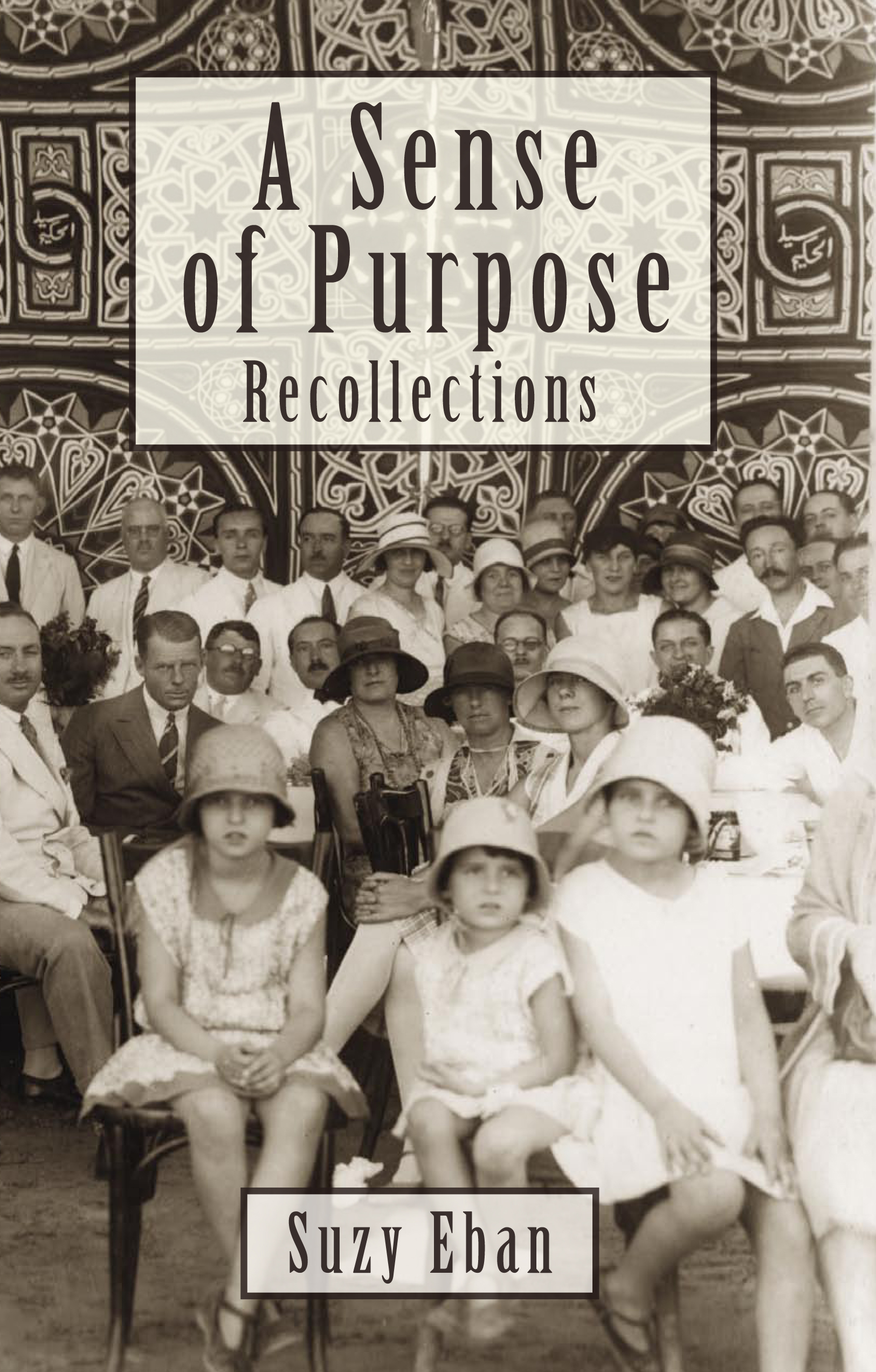

Eban certainly begins on the right track. In fact, the first 100 or so pages of her narrative are absolutely scrumptious. Possessed of a sharp eye and a deft hand (parts of this section were published decades ago in an earlier form in The New Yorker ), Eban excels at conjuring up the sights, sounds, scents and other sensuous evocations of her childhood in the 1920s and ‘30s in Ismailia (where her Palestinian-born father worked as an engineer for the Suez Canal Company ); visits to her maternal and paternal grandparents, who were Zionist pioneers in Motza, outside Jerusalem, and the Neve Tzedek quarter of Tel Aviv; and her adolescence and courtship in Cairo by a handsome, polyglot, former Cambridge don whom the British Army dispatched to the Middle East during World War II to serve as its liaison with the Jewish Agency (the political leadership of the Palestinian Jewish community ) in Jerusalem.

Suzy (nee Shoshana Ambache ) and her three siblings were slightly offbeat products of the Levant, if only because Hebrew was the language spoken in their home, while the girls were educated in French, first in a convent school in Ismailia and then in a secular private school, after the family had moved to the tony Zamalek section of super-cosmopolitan Cairo in 1936. Describing the city as a pulsing hub of “Armenians, Circassians, Copts, Greeks, Jews, Lebanese, Syrians Turks,” all adding flavor to the mostly impoverished, indigenous Muslim population, she explains that the conventional lot of a daughter of the middle or upper class was early marriage and “a life of leisure and acquisitions, bridge parties, fittings at the dressmaker and the lingere, tea at Groppi’s, the Sporting Club and the usual summer months in Europe.” But “by instilling Zionism in their daughters, together with a feminist sense of equality and an interest in higher education,” she writes, Suzy’s parents had effectively doused their desire for such a lifestyle. And although her parents had given no thought to “equipping any of us [girls] to enter a profession,” she continues − and the war at any rate prevented them from pursuing their education abroad − Suzy enrolled first in Fuad-el-Awal University, where select lectures were held in French, and afterward in the American University, for courses taught in English. At her father’s insistence, she also began taking private lessons in Arabic.

In the spring of 1943, Suzy met Aubrey Eban, who, well before reaching Palestine as a 28-year-old British army captain, was already a committed Zionist. (In the late 1930s, while lecturing in classics and Oriental languages at Cambridge, Eban had been hand-picked by Zionist Organization president Chaim Weizmann to fill in for the head of the Jewish Agency’s political department in London. ) Apparently smitten with her, Aubrey shuttled between Palestine and Egypt for two years, “courting me in total single-mindedness,” Eban recalls. He, in turn, helped her to see “what it was that I truly wanted,” she declares. And yet she harbored qualms: “There was ‘something different’ in this man, in his mind and even more so in his sensibilities,” Eban writes, “and I wondered if I was capable of meeting the demands of a life with him.” Initially she was wary of choosing a mate whose career would be dedicated exclusively to “Jewish political life.” His choice of that vocation, she tells us, had also puzzled his friends. Some deemed it, “among all the opportunities for which he was equally equipped,” to be “a reckless mistake,” she reports. “’Too quixotic!’ they said. ‘Squandering a great talent on a parochial scene.’”

She also fretted about their coming from “quite different” cultural backgrounds. “I was from the Middle East,” with a “strict French education” and “Palestinian emphasis,” she explains, and “my home had always offered upper-class bourgeois comfort.” Aubrey came from “the West ... from a traumatized home that had left him with an inner reserve.”

Indeed, after their marriage in March 1945, “I would often feel challenged by the demands of our coming from two different cultures,” she writes, but refrains from enlightening us any further. Moreover, she assumed that “Aubrey must have felt something similar, despite his total commitment to Israel,” she adds rather incongruously, “and the fact that he chose it and was not driven into it by circumstances.”

Is Eban still talking here about the disparities of disposition between the spouses? Or is this an early intimation of a yawning cultural gap between the couple and the “parochial scene” to which they had harnessed their future? It’s impossible to say, for Eban’s style grows increasingly opaque as she continues: “Separately we had each experienced the Middle East from a cosmopolitan reality and now we shared it together. Our separate orientations were sometimes conflicting. Each element would pull us back to our own familiar grounds. However, there was no need to give up anything and we did not, but a magic act was demanded to keep it all together without a sense of renunciation or deprivation.”

Striking the right chord

That descent into ambiguity is, unfortunately, a portent of things to come. For once the narrative shifts to a description of her life as Mrs. Aubrey (latter Abba ) Eban, “A Sense of Purpose” loses its focus and vision of what, from the author’s unique perspective, is truly worth sharing with us. After all, writing Israel’s history, and Abba Eban’s role in shaping it, was her husband’s metier − and he practiced it with panache in any number of books and television documentaries. What insights can his wife add by portraying her observations of life at his side?

One must often work hard to distill them from her narrative. Eban’s three chapters profiling the wives of prominent Israeli political figures − Vera Weizmann, Rachel Yanait Ben-Zvi, and Paula Ben-Gurion − suggest that she was concerned about striking the right chord in this same role by tailoring it to her own strengths. Her position was not analogous to any of these women: Mrs. Ben-Zvi was an ideological force in her own right, while Mmes. Weizmann and Ben- Gurion had sacrificed careers to minister to their husbands’ needs. But for all her elegance and polish, which had surely been enhanced during her husband’s 12-year ambassadorial stint first in New York at the United Nations and then in Washington, D.C., Suzy Eban was no trophy wife. In some of these pages, she comes through as a selfpossessed, creative, even assertive woman of the world who, as its president, put the Israel Cancer Association on the map. She also had a pronounced aesthetic sensibility (among the book’s most ebullient passages are those describing her delight at exploring the postwar art scene in New York ), which she was able to express as a member of Tel Aviv Arts Council.

For the most part, however, while her husband was immersed in haute politique, Eban filled her days by renovating official residences, organizing dinner parties, and attending state events − none of which makes for particularly compelling reading. The dinner parties, at least, might have been highly engaging fare had she regaled us with some of the scintillating or scandalous conversation around the table. But with the sole exception of a vignette of British Foreign Secretary George Brown (1966-68 ) getting “plastered” before dinner at the Eban residence in Jerusalem, proceeding to abuse his own ambassador, and being ordered by the latter to leave, as Mrs. Brown dissolved into tears in the drawing room, she does not open a window onto this corner of her world.

And reticence of this sort is not atypical. In discussing the challenges and vicissitudes of her husband’s career, for example, Eban barely grazes such potentially fascinating subjects as his obligation, as an ambassador and a minister, to defend policies with which he sometimes disagreed. Indeed, only once does she even vaguely allude to his dovish views. So when she comes to discuss his humiliation and rejection by his party colleagues − first in 1974, when prime minister Yitzhak Rabin ended Eban’s eight-year tenure as foreign minister and offered him the junior post of information minister; then in 1988, when the Labor Party’s Central Committee failed to slot him into any of the first 20 places on its Knesset slate − we’re deprived of any insight about why this extraordinarily successful man had ceased to be deemed a political asset. Was it due to his left-leaning views? Or could it be that he was a victim of the cliquish character of the Labor Party, in which a foreign-born, urbane intellectual who lacked any connection to thepre-state Palmach or Haganah − and spoke Hebrew with an atrocious accent, to boot − could not long thrive without the backing of his champions (Levi Eshkol and Pinhas Sapir ) of a bygone era?

Circuitous narrative

Rather than offer us her own take on this cardinal question, Eban defers to the political eulogy penned by the poet Haim Gouri, who stated outright that “even after his many years [in Israeli politics, Abba Eban] was sometimes considered an outsider. Different in his culture and his tongue. Somewhat out of place in the landscape.” I can’t help thinking how much more engrossing this chronicle would have been had Eban grappled with this question head on.

There’s another drawback to her narrative: To explain the context of certain highlights of her husband’s career, Eban occasionally provides brief overviews of events. Unfortunately, as a historical narrator she is often erratic and unreliable. Her chronology of the lead-up to the Six- Day War, for example, is garbled. While she lauds the historic impact of her husband’s June 6, 1967, speech before the UN Security Council, she fails to provide even the briefest precis of what he said. And the book is marked by factual errors ranging from trivial (that Jordan’s King Abdullah I was assassinated in the Dome of the Rock, rather than the Al-Aqsa Mosque ) to mortifying (that Rabin became prime minister in 1974 as the result of a general election precipitated by the resignation of Golda Meir’s government, when no such election took place ).

After Abba Eban was edged out of politics − at, we should probably note, the quite respectable age of 73 − he did not slide into obscurity. On the contrary, he went to write his second tome on Israeli history, two books on diplomacy − a subject he also taught at Princeton, Columbia, and George Washington universities − and two TV documentary series about Israel, which he also narrated.

All told, until his death in 2002, the couple shared what reads like an enormously rich life in which they exploited their potential to the full. Yet Suzy Eban chooses to end her book on a jarringly bitter note. “Many other possibilities may have comfortably absorbed us, but Zionism surpassed them,” she writes. “We paid a heavy price for this total merging into this political reality.” Given her own portrayal of the array of activities in which they engaged and excelled, separately and together, I’d say that summarizing judgment is pretty harsh. But as in earlier instances of glancing off intriguing subjects, Eban fails to spell out the source of her grievance − what, in her eyes, their shared life’s journey lacked, or what alternate dream either of them had sacrificed to fulfill their sense of purpose − and thereby clarify what she means by that “heavy price.”

It’s regrettable that the aides Eban thanks in her acknowledgments were not able to draw out of her a more direct, explicit and thus satisfying treatment of the issues and themes treated so obliquely here. That much talent lay behind the writing of this book is amply attested by its opening chapters. As the narrative proceeds, however, that talent is served up raw, insufficiently tempered by craft, which is a pity.

Ina Friedman, a correspondent for the Dutch daily Trouw, is co-author of “Murder in the Name of God: The Plot to Kill Yitzhak Rabin.”

© Haaretz 2008